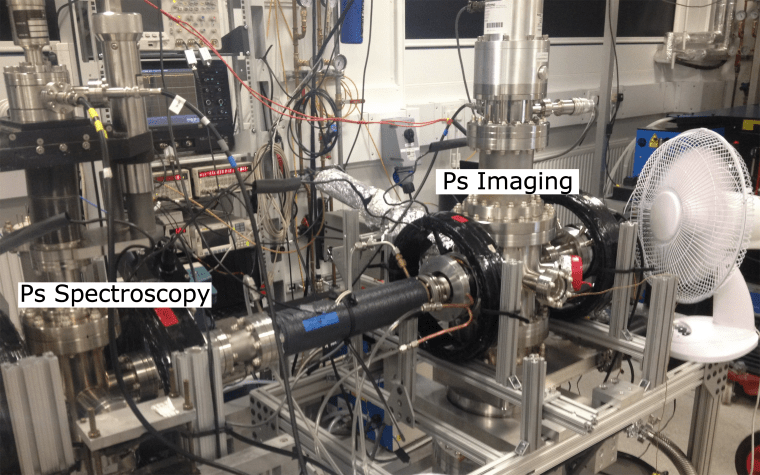

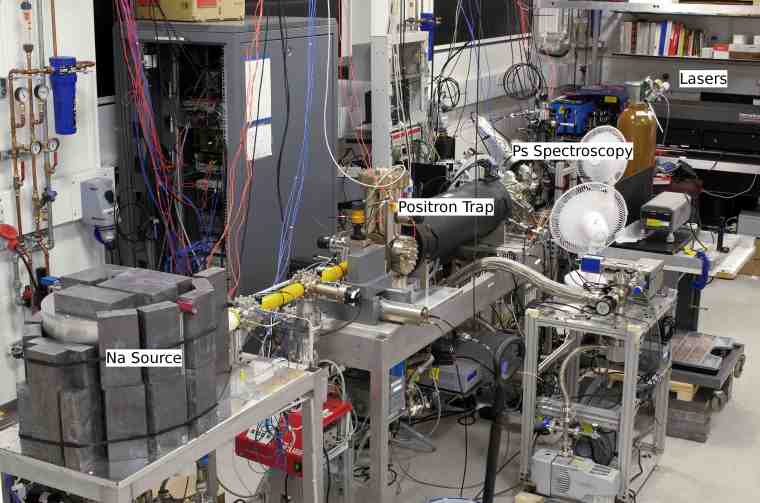

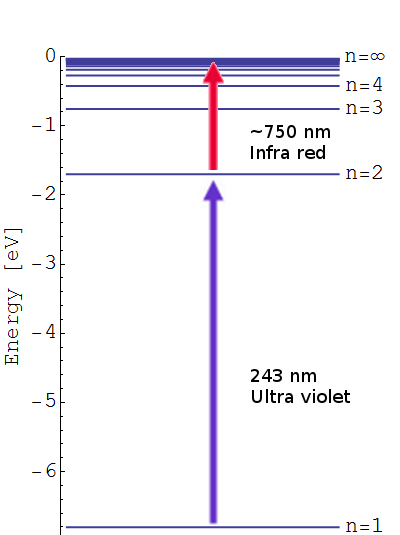

The positronium spectroscopy experiments we perform are contingent on our ability to form and bunch dense clouds of positrons (anti-electrons). These are implanted into porous silica where they pair up with electrons and form our favourite exotic element, Ps (which we then photo-ionise with lasers before the two components have chance to annihilate one another).

It’s been 24 years since the first buffer-gas trap [1] was used to collect positrons using a combination of electric and magnetic fields in a configuration known generically as a Penning trap. The positron accumulation device is often termed a ‘Surko Trap’ after its inventor Cliff Surko, and there’s detailed information about how they work on his site.

The magnetic field lines of a solenoid guide a low-energy positron beam through a series of cylindrical electrodes that have been biased with voltages to create an electric potential minimum (along the axis of the magnetic field) – see figure below. These fields alone are not enough to capture positrons from the beam, as those particles with enough energy to enter the trap can also escape it. Admitting a small amount of nitrogen into the vacuum chamber allows positrons to lose energy as they traverse the trap via inelastic collisions with the buffer-gas molecules, resulting in confinement. Unfortunately positrons are also lost to annihilation with electrons in the gas. Surko traps feature several sections with the pressure in each optimised to either capture (higher pressure: good chance of an inelastic collision) or to keep (lower pressure: less chance of annihilation) positrons, which gives the trap its characteristic asymmetric shape. Thanks to years of optimisation and refinements [2] these devices can accumulate hundreds of millions of positrons from a small radioactive source in just a few minuets (our fairly small trap is capable of capturing roughly half a million e+ in 1 s). Pulsing the electrode voltages ejects the positrons from the trap in a dense, time-focussed (<10 ns) cloud that’s ideal for creating Ps atoms.

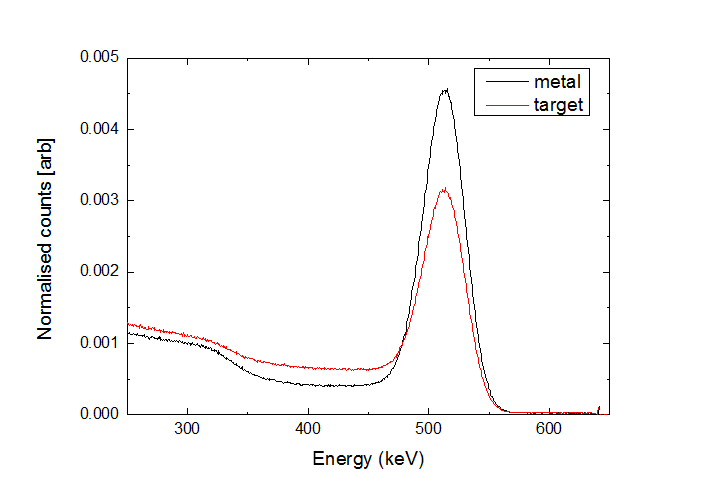

The details of how the positrons interact with the nitrogen are critical for optimisation of the trap. The likelihood that a positron will have a collision with a nitrogen molecule is related to the pressure of the gas and the scattering cross-section: a hypothetical area that describes the apparent “size” of the molecule. The scattering cross-section has numerous components that correspond to different types of interaction (elastic collisions, various types of inelastic collisions, ionisation, direct annihilation, Ps formation, …. etc) with some interactions more likely than others. However, these cross-sections can vary significantly depending on the energy of the collision.

Nitrogen is used in Surko traps because there is a small range of energies (around 10 eV) where inelastic scattering by exciting an electronic transition in the molecule is reasonably probable, compared to annihilation. After the positrons cool below the energy needed to excite the electronic transition, further cooling relies on exciting the vibrational states of the molecule, for which the cross-section is rather small. To speed up cooling we use a second gas, tetrafluoromethane (CF4), which has a much larger cross-section for low-energy inelastic collisions with positrons [3].

Recent Monte Carlo simulations of Surko traps offer a way to further optimise and improve trap designs without the need to manufacture dozens of prototypes.

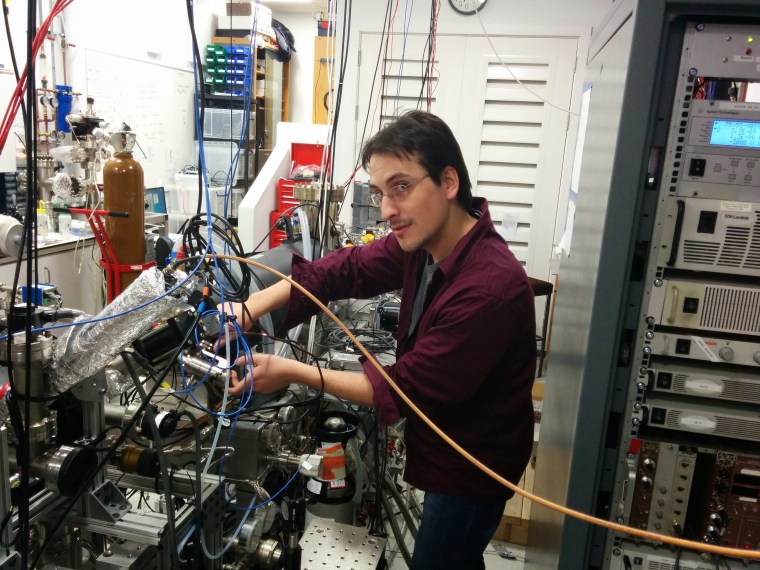

This past week Srdjan Marjanovic, a PhD student at the University of Belgrade, visited UCL to test some of the simulations he has been working on (see above) using our positron trap. One suggestion he made is to use CF4 for trapping, in lieu of nitrogen, the logic being that for the energies where inelastic collisions dominate many loss mechanisms are suppressed. The main difficulty, however, is that many more collisions are needed to successfully capture the positrons, as the energy exchanged to excite vibrational transitions in CF4 is roughly 40 times less than for the electronic transition usually exploited with N2. Unfortunately we were unable to adapt our trap to work efficiently with CF4. Nonetheless, by trying we have learnt more about how our trap works and – most importantly – Srdjan has new data he can use to refine his simulations.

Photo. Srdjan hard at work on the positron beam.

Refs.

[1] Surko, C.M., Wysocki, F.J., Leventhal, M. and Passner, A. (1988). Accumulation and storage of low energy positrons. Hyperfine Interactions, 44:185–200. http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/BF02398669

[2] Surko, C.M. and Greaves, R.G. (2004). Emerging science and technology of antimatter plasmas and trap-based beams. Physics of Plasmas, 11(5):2333. http://dx.doi.org/10.1063/1.1651487

[3] Natisin, M.R., Danielson, J.R. and Surko, C. M. (2014) Positron cooling by vibrational and rotational excitation of molecular gases. J. Phys. B 47: 225209. http://dx.doi.org/10.1088/0953-4075/47/22/225209